HISTORY LESSONS

Comparative Literature

Course: Science Fiction in Hispanic Contexts - SPAN 398

Concordia University

March 2024

Story: The Circular Ruins

Author: Jorge Luis Borges

Date: 1940

Kind: Theology, Philosophy, and Literature

Genre: Fiction

What are the Circular Ruins? There really is no other question here.

Most prominently, the figures, images, and premises presented in Jorge Luis Borges’ short story ‘Las Ruinas Circulares’ can be read, figuratively, as an allegory to the evolution of Consciousness. More precisely, and this is my account, the History of Western Consciousness. Nonetheless, the available interpretations of this story are as multiple as the literary, philosophical, and theological references it contains. Its contents and their sequence point to myriad references ranging from Antiquity to Modern cosmovisions. The most crucial are perhaps those allowing the interested reader to trace a conceptual lineage of models of Knowledge and Belief (Philosophical and Theological) across Western History. Starting perhaps from Late Antiquity, its later use in Catholicism and its Pagan mirrors, and its evolution throughout the Enlightenment to Modernity. Here I am less interested in tracing this genealogy myself, as for this would require a thorough turn into the cul-de-sac of interpretation and adjudication, rather, I prompt we dive right into the night of this unanimous dreamer with intentions of finding nothing in particular; for ultimately, we’ve been called upon to experience two of the most treacherous unknowns: the intimacy of humankind in the obscurity of its religious existence, met by the light we place upon the deep.

This paper is composed of fragments expanding on particular passages from the story. These passages, I perceive, point to different orderings of Self and Universe, Matter and Idea, Positionality and Movement, and what else, we shall evaluate the mode of creation our dream-creator devises at each stage. For this, I will be making considerable use of another chunk of text that is contemporary to this story, Bertrand Russell’s The History of Western Philosophy (1945) and relating the contents of the story to the contents of the History of Western thought.

note: with ‘Western Thought/Consciousness’ here, I am referring to it in its original sense, as the evolution of European universality as a discriminate system, I am not integrating its alterations upon the clashing with the Americas and the subsequent syncretism. Although they may certainly apply. I want to advert that it is a conscious decision to abstain from building metaphorical references linking the contents of this story to historiographic accounts of colonial syncretism, or to Borges’ condition as a cross-continental Hispanic literate, or the political context in which the story was written.

…

NIGHT 1. COSMOS

SUBJECTS: UNIVERSE & SELF; ANATOMY, COSMOGRAPHY & MAGIC; THE DAWN OF THE METAPHORIC BEING; ASTROLOGY

“Nadie lo vio desembarcar en la unánime noche, nadie vio la canoa de bambú sumiéndose en el fango sagrado, pero a los pocos días nadie ignoraba que el hombre taciturno venía del Sur”

(…)

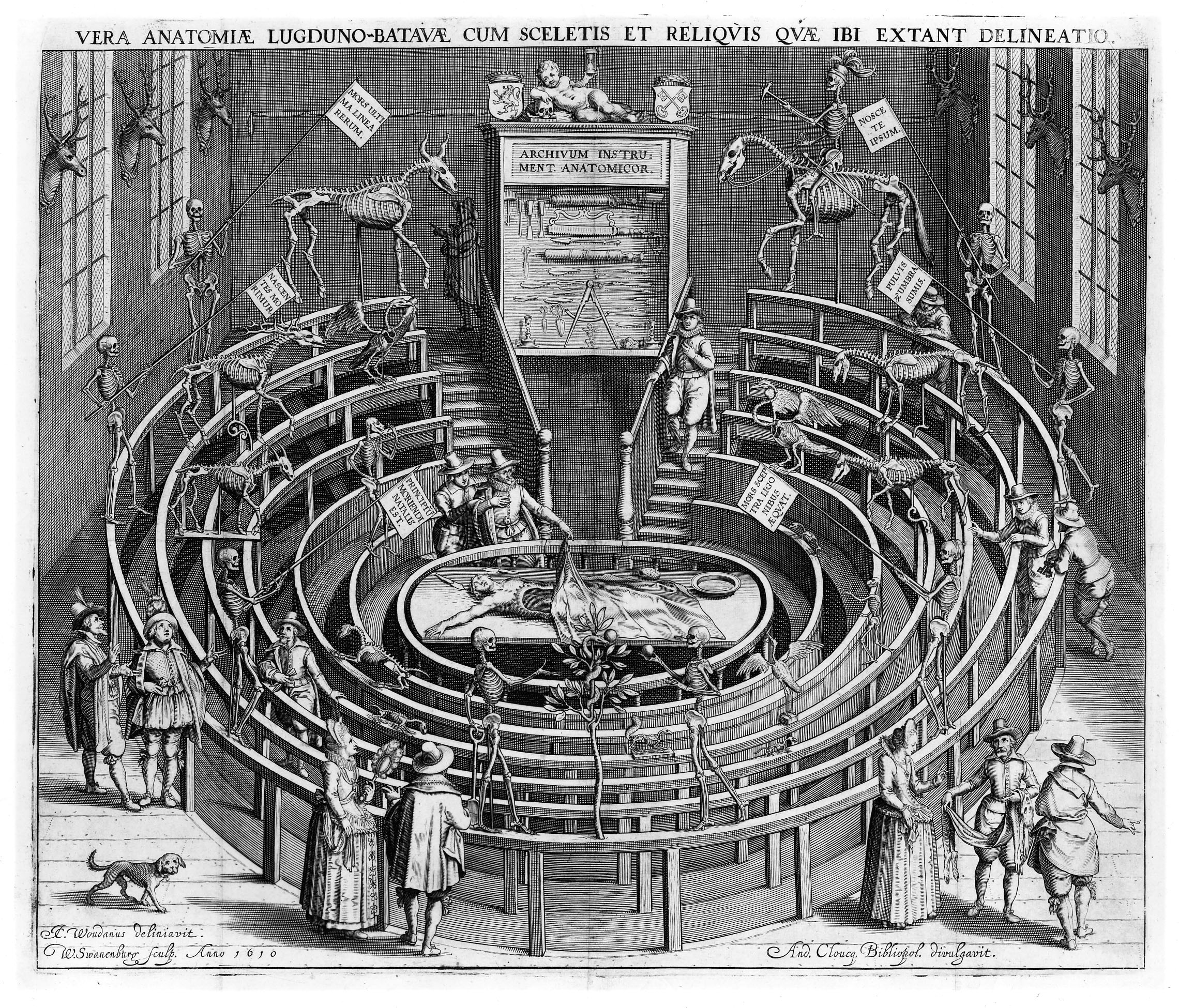

Al principio, los sueños eran caóticos; poco después, fueron de naturaleza dialéctica. El forastero se soñaba en el centro de un anfiteatro circular que era de algún modo el templo incendiado

(…)

El hombre les dictaba lecciones de anatomía, de cosmografía, de magia”

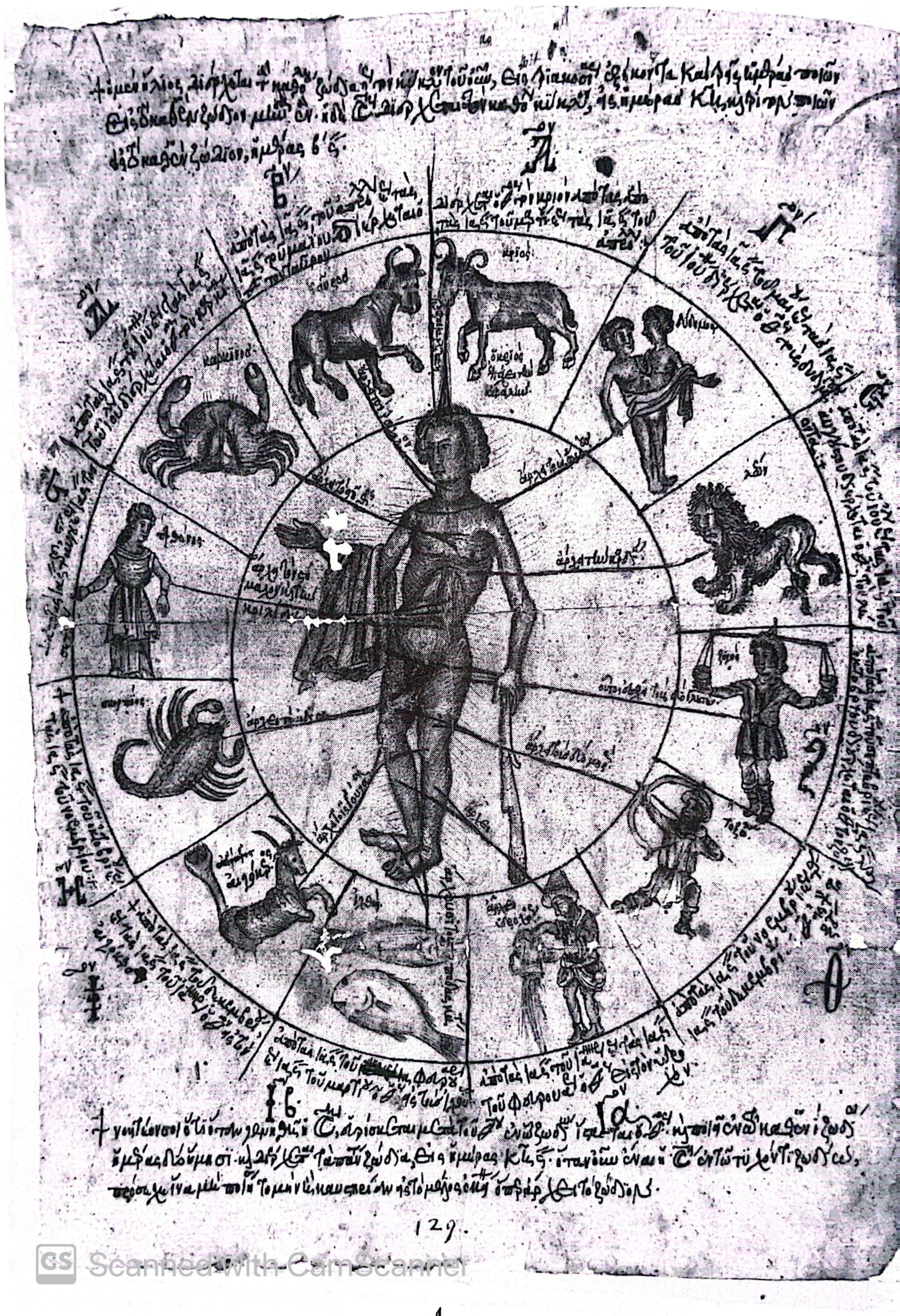

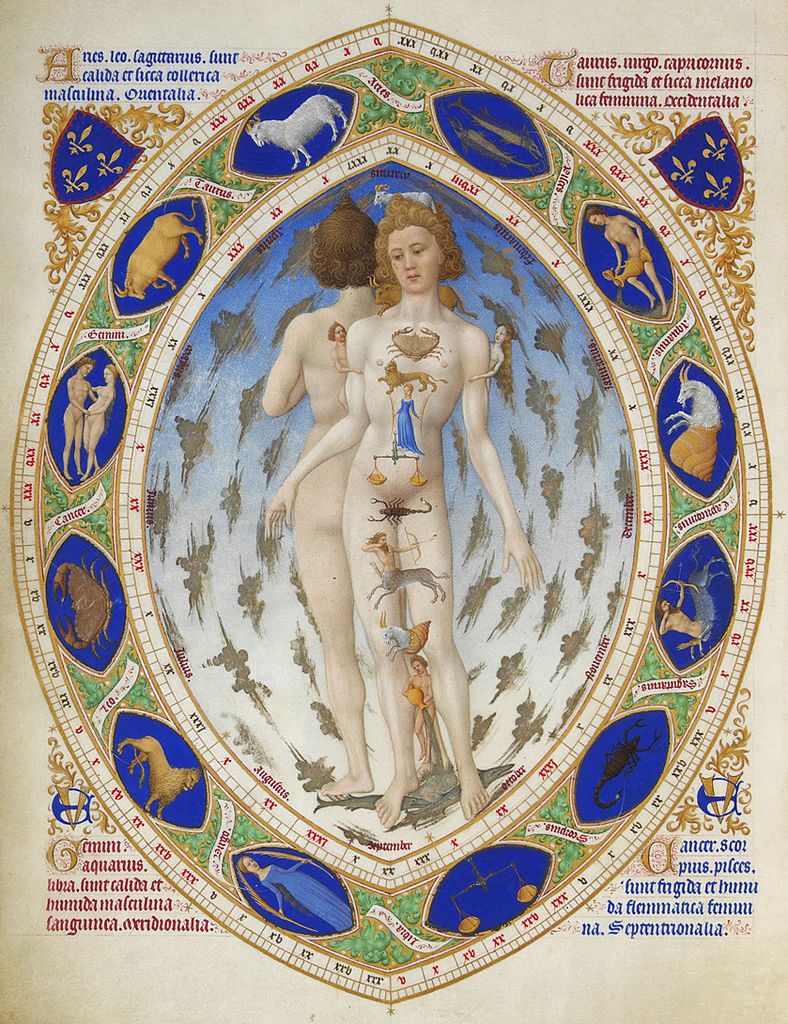

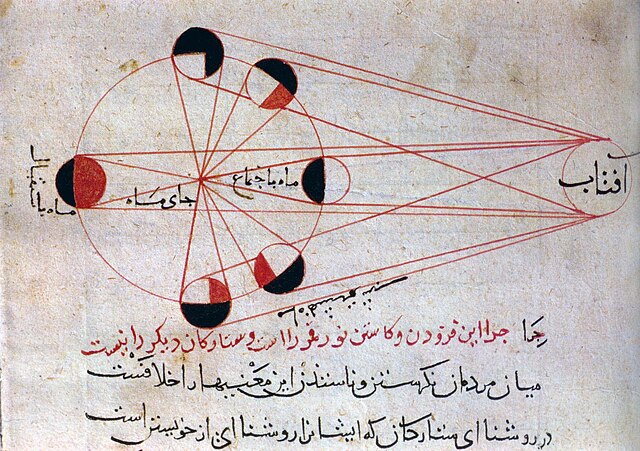

The articulation: anatomy, cosmography, and magic is not random. It rather refers to a very particular cosmic epistemology which interpolated, perhaps as ‘a technoscientific paradigm,’ between late antiquity and the Medieval period; where it gradually faded away to the rise of Christianity’s monolithic universe. Nonetheless, its planetary observations—inner interferences about the Self, World, and Sky, were to remain close to the core of the ‘systems of Belief’ that would succeed it; not only in the subliminal imaginary and the evolution of iconography, but materially present in ever-returning idealism. To be precise, this particular cosmovision conceives the existence of a macrocosmos and a microcosmos (the human Self) to be inherently connected or belonging to a celestial, singular system; whose relations can be grasped through the observation, study, and calculus of the celestial bodies (planets; stars) that appear in the Celestial sphere (The Sky), for their movement had effect on the movement that happens in our material world (though, this study is more Metaphorical than Physical). To put it simply: the parts of ourselves are connected to the parts of our universe.

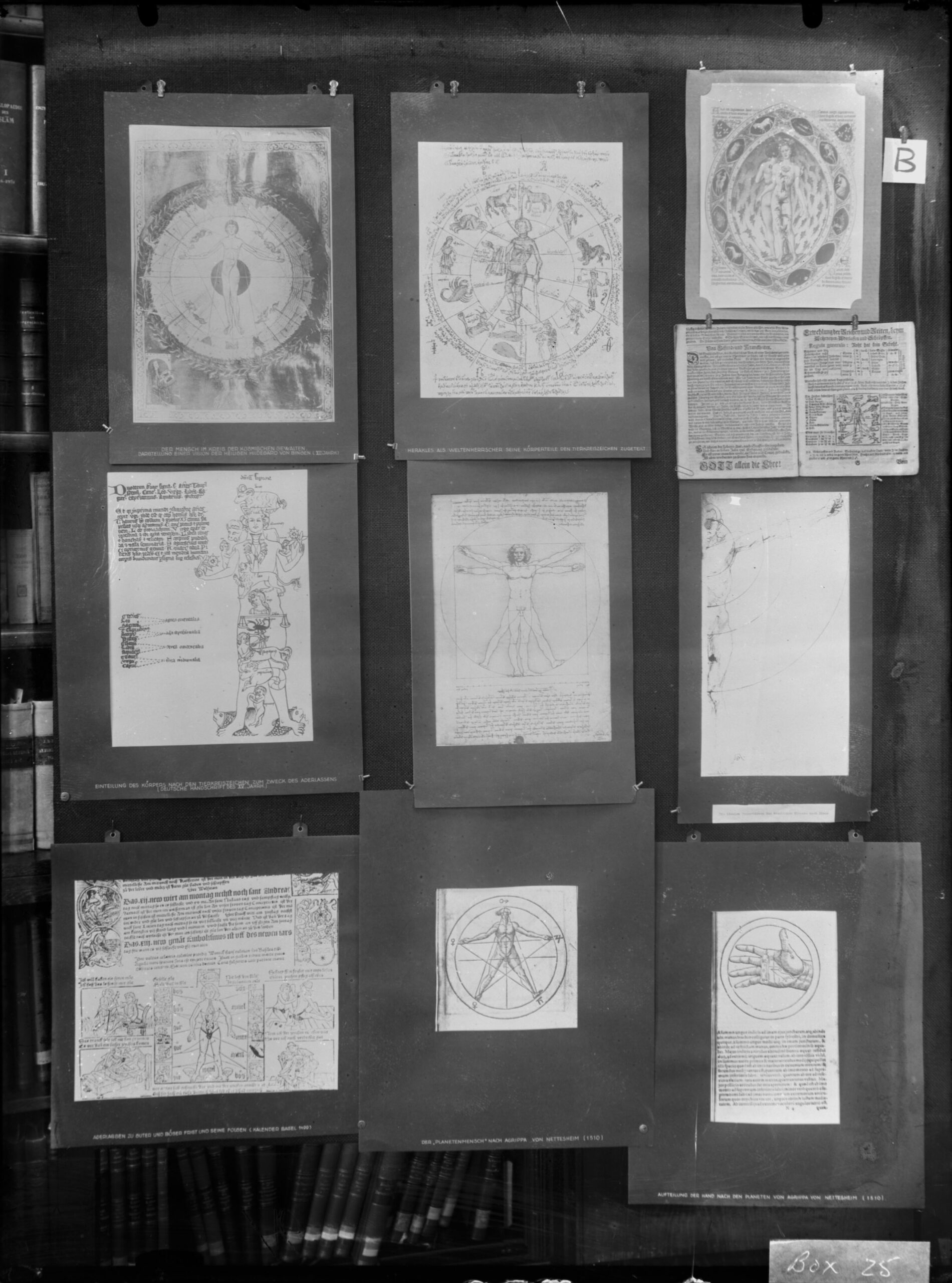

Astrology, as we now refer to this epistemology, belongs to the scientific paradigm established for the time that concerns this particular passage, one in which cosmology was evolving less substantial and more structural. Some might argue, it had provided the structural basis (structural thinking) for Catholic/Christian theology that would later regard it as pagan. (Notwithstanding, Christians and Pagan, as we shall learn later, would often come to find common ground in the theological and scientific study of interplanetary phenomena). In some way, the metaphorical potential of Antique cosmic imagination and its imagery permeated not only iconographically throughout the dark ages, but also provided support for Theology to never abandon fully the Scientific inquiry. Aby Warburg, who died in 1919 leaving incomplete what would have been one of the greatest achievements in Art History, had devoted his life to tracing the subliminal lineage of celestial iconography from Antiquity to Late Rennaissance. One of the few matured and recorded projects that have been recently translated is his research on the sphaera; which could be understood as the study of the iconographic transmission of the study of the Skies. His historizing is somewhat entangled and academically obscure, nonetheless, invested and genealogical, and for the better part, the sphaera facilitated an iconographic study of Cosmography and its influence in the systems of Belief that would dominate until the Enlightenment.

In a general sense, he conceived Astrology as a sort of relativism that evolved from the detachment of Magic and structural cosmology. To better understand this notion, he provides a very clear definition of the technoscientific explanation of Magic in this early paradigm: “Magic is, in the sense of late Antiquity, simply applied cosmology. This is, the application of an Identity principle between subject and world that leads to the practice of manipulation—the idea of the microcosmos.” The paramount representation of this is embodied in the icon of the Zodiac Man. Which is, in some way, a visual representation of Self and Universe. What the Zodiac paradigm conveys is that each organ is connected to a zodiac sign; and thus, the radiance of astral bodies influences our respective organs.

The difference between Astrology and Applied Cosmology can be understood by analyzing the misleading relation between metaphor and designation. The astrological doctrine fails, according to Warburg, for it abandons the metaphoric being to the designation sense. (69) He used the sociological term, Loi de participation (which in psychology comes about simply as the ‘social manifestation of reality;’ in sociology as that the study of consciousness chiefly requires that it be studied situated in its particular social matrix) to describe the way astrology marks a detachment from the metaphoric Being and establishes itself as a social consciousness, which manifests effects on its own but is abandoned by the course of the theological project of Being—becoming, at its best, conscious of itself as a partial knowledge.

Unsatisfied with his original creation, our dreamer-creator abandoned his initial projects, and proceeded to dream of other deities, which were multiple nonetheless, or at least they seemed, for he could not avoid himself from the irrevocable presence of their bodies, which were all he knew. Hesitant to detach his imaginary from the natural cosmos and its bodies as a separate consciousness, he was to become pagan in his own universe. He dreamt a Man and his pulsing heart, and rather than teaching anatomy, he embarked on the anatomical task of constructing this Man which would be made of matter (heart; lungs; skeleton; eyelids; hair), but that would also be made of something else, of something deposit between the heart, the symbol of a planet, and another unpronounced chief organ: “luego retomó el corazón, invocó el nombre de un planeta y emprendió la visión de otro de los órganos principales.”

NIGHT 2. GENESIS

SUBJECTS: THE CREATED WORLD; SOUL & MATTER; PLOTINUS & THE GNOSTICS; THE PLANETS’ BURDEN

“Comprendió que el empeño de modelar la materia incoherente y vertiginosa de que se componen los sueños es el más arduo que puede acometer un varón, aunque penetre todos los enigmas del orden superior y del inferior

(…)

Juró olvidar la enorme alucinación que lo había desviado al principio.

(…)

Luego, en la tarde, se purificó en las aguas del río, adoró los dioses planetarios, pronunció las sílabas lícitas de un nombre poderoso y durmió. Casi inmediatamente, soñó con un corazón que latía.

(…)

Deliberadamente no soñó durante una noche: luego retomó el corazón, invocó el nombre de un planeta y emprendió la visión de otro de los órganos principales. Antes de un año llegó al esqueleto, a los párpados. El pelo innumerable fue tal vez la tarea más difícil. Soñó un hombre íntegro, un mancebo, pero éste no se incorporaba ni hablaba ni podía abrir los ojos. Noche tras noche, el hombre lo soñaba dormido.

En las cosmogonías gnósticas, los demiurgos amasan un rojo Adán que no logra ponerse de pie; tan inhábil y rudo y elemental como ese Adán de polvo era el Adán de sueño que las noches del mago habían fabricado.”

demiurge (/ˈdɛmi.ɜːrdʒ/): an artisan-like figure responsible for fashioning and maintaining the physical universe. Corresponding to Platonic, Neopythagorean, Middle Platonic, and Neoplatonic Philosophy; adopted by the Gnostics.

Plotinus (CE 204-270), the last of the Great philosophers of Antiquity, or at least in the account of Philosophy Historian Bertrand Russell, is described as not particularly akin either to astrologers nor magicians. Moreover, although with a considerable degree of streaming influence, Plotinus’ doctrines would oppose that of the preceding Gnostics. It would do so in a way that is relevant to grasp the events described in the above passages as imagined by our dream-creator. Let us detain ourselves here to consider the modes of creation at play in this passage; for it makes apparent references to an evolution (shift) in the paradigms of cosmic Genesis.

For as the astrologers and magicians, it concerned the problem of Sin and ‘free will.’ For Plotinus thought of Sin as a consequence of free will. Nonetheless, he did not oppose either the scientific capacities of astrology nor he was free from superstition in his philosophy, rather, he simply regarded them (the astrologers and magicians) as determinists; as if, for instance, the metaphysical truth of the astrological system rendered human incapable of Free Will, and thus, of Sin.

For as the Gnostics, Plotinus would have rejected some of the most fundamental components of their doctrine. For the most part, in two main respects:

1.) The Gnostics believed that the material world was created by a dark deity named Ialdabaoth (a platonic Demiurge). Often presented as a lion-headed snake. What is important to understand about Ialdabaoth is that was born from Sophia (Wisdom, the lowest ranked divinity), in a rebellious attempt to make a copy of herself; Ialdabaoth is thus born as an imperfect, copy of a conspiring deity. In short, the Gnostic Genesis implies that Ialdabaoth first produced Matter; he brought Adam into existence by breathing into him his own Soul, he then created the Serpent (Ophiomorphos), often referred to as the Serpent of Knowledge, which was to become the embodiment and origin of all Evil. Thus, while matter preceded evilness, the creation of the material world results from the device of a macabre lower entity, and in a sense that Knowledge, Evil, and Soul seem to articulate an original trinity.

Although not free of difficulties, Plotinus rejected this idea. He firmly believed that Matter was created by the Soul, and that Soul descended from a Divine memory. The Soul was, in his sense, immortal in its transmission. Sticking to his Platonic foundations, he conceived that Soul had no material body-form nor it was matter, it was Essence, and Essence, like Platonic ideas, is eternal. He thus believed that when the soul leaves a body it necessarily enters another body. And a Soul was subject to the Good and the Evil (Sin) and carried the burden of its past life into the next. Thus, the evolution of human Being across the centuries is the evolution of Soul, tracing all its way back: The soul creates the material world (the visible world) from the memory of the divine.

2.) The Gnostics rejected the idea that the Sun, the Moon and the Stars were associated to some sort of positive divinity; since they thought they resulted (as the rest of the cosmos) from evilness. Whereas Plotinus firmly believed that the celestial bodies not only resembled, but were themselves God-like. Before Beauty and its inspiration came to be demonized by the Church in the years that succeeded Plotinus, it had played an important role for the late-ancient philosophers, him in particular, to articulate a version of the cosmos in which heavenly bodies inspired a supreme Beauty; and Beauty, as it streams from the Divine, was fundamental in the organization of reality.

Nonetheless, something that Plotinus and the later Gnostics find a common ground in their versions of genesis is that they both consider the universe, or the material world, as a copy of an original. For Plotinus, this is as beautiful as it can be, since the Original is eternal in its beauty. For the Gnostics, genesis was a mistake.

We can make better sense of this by Plotinus’ own explanation:

This All that has emerged into life is no amorphous structure—like those lesser forms within it which are born night and day out of the lavishness of its vitality—the Universe is a life organized, effective, complex, all-comprehensive displaying and unfathomable wisdom. How, then, can anyone deny that it is a clear image, beautifully formed, of the Intellectual Divinities? No doubt it is a copy, not original; but that is its very nature; it cannot be at once symbol and reality.

(…) Such a reproduction there must necessarily be—though not by deliberation and contrivance—for the Intellectual could not be the last of things, but must have a double Act, one within itself, and one outgoing; there must, then, be something later than the Divine; for only the thing with which all power ends fails to pass downwards something of itself.Plotinus, Tractate on the Gnostics (II, 9, 8)

At this point of the story, we are dealing with a sort of genesis in which our dream-creator has partaken from his planetary Gods and moved forward to dream of a new Being, a copy of himself nonetheless. As we will see in the following two sections, he creates him in his image, and in a mirror version of its own environment, following the instructions of a strange deity.

NIGHT 4. COPY

SUBJECT: IMPRESSION & IDEA; PROJECTION; FLESH & IMAGE

“al cerrar los ojos pensaba: Ahora estaré con mi hijo. O, más raramente: El hijo que he engendrado me espera y no existirá si no voy.

(…)

Una vez le ordenó que embanderara una cumbre lejana. Al otro día, flameaba la bandera en la cumbre.

(…)

Comprendió con cierta amargura que su hijo estaba listo para nacer – y tal vez impaciente.

(…)

Antes (para que no supiera nunca que era un fantasma, para que se creyera un hombre como los otros) le infundió el olvido total de sus años de aprendizaje.”

Following the effigy’s instruction, our dream-creator felt sure that his son was ready to be drafted from dream to the material world. And so he had so thoroughly prepared him for the real world by teaching him lessons thought required that, once prepared, forget all he had learned to be born in reality; for no one is born corrupted with the burden of consciousness and History. Yet, the conditions for his son’s being, required too a higher level of secrecy and purity: that he never learns what he truly is; ultimately, a spectre, a ghost, an impression imagined in the dreams of someone else. He must never learn that his existence is not real.

This very idea, that one can exist in the real while being yourself not real, is what returns to inform our magician he was wrong all the way. The phantasmagoric or hauntological assumption that someone can be a ghost, and a ghost can be a Being, as long as it has experience and is perceived by another entity, poses a turning point to a longstanding convention of post-Enlightened Being: do I exist because I can think of myself, or do I exist because someone else is able to perceive me? This is a question from which philosopher David Hume (1711-1776) would reanimate the Descartesian paradigm of existence.

In his seminal work, Treatise of Human Nature (1739), Hume opens by making a distinction between “impressions” and “ideas.” He thinks an impression is forceful, longstanding, violent, whereas the idea is a lesser, fainting image that lives in the memory and the imagination. He argues a simple idea can be traced to an original impression. According to him, an idea resembles and evolves from an original impression, it is, in a sense, merely a mental reproduction. He then argues that complex ideas do not necessarily rely on an original impression. For one can imagine the complex morphology of a chimera that might be a tiger, a horse, a bull, and a rose, but that is also a statue and also a prophet, without never having truly seen one. His main argument could be understood as trying to debunk the idea of that there is substance to Self, for if we stick to the deductions of his treatise, there is no impression of the Self, therefore, no original idea of Self.

Bear with this notion for it is the turning point of this narrative. The backstab of the story.

What is at stake here, is the question of whether his son is brought into reality as an impression, an idea, or a substance. For Hume, the “Self” is a bundle of perceptions. The implications of this in Metaphysics were important, Russel explains, for they got rid of what remained of “substance” in the discussions over existence, at least in some fields like psychology. In a way, he is approaching a sort of epistemology similar to Haraway’s, for is one primarily concerned with the question of Probability and the relative/subjective nature of Empirical knowledge that presents itself as the opposite. In a section of his Treatise “Of Knowledge and Probability,” he opens up the idea of “uncertain knowledge,” or “probable” knowledge, which is, in the more general sense, almost all sort of knowledge: obtained from the evaluation of “empirical data by interferences that are not demonstrative.” The only sort of knowledge that exists outside this paradigm of demonstrative uncertainty is, according to Hume, that of direct observation, the logical, and the mathematical. We now know these forms of knowledge are, too—even mathematics—only verbal, thus, relative. At the bottom line is the argument that the Self (or, the knowledge of the Self) has no substantial quality that grants it unicity other than an exterior perception of such. He explains that every time he makes sense of himself, it is more than anything stepping into the perception of the other. He cannot observe himself if it is not through the other’s perception of him. This moves us beyond the Descartes paradigm “I think therefore I am,” to “I am because others think me.”

And so, the dreamed son was born unadvertised and in a remote location from his father-creator, but dwelling in a similar condition: induced by the faraways, without questioning the integrity of its being nor the lineage of its capacities, abiding solely by the omnipotence of their own mind, they are both referred to as Magicians. We are told this happened when two anonymous figures came to inform our dreamer about a faraway magician who lay in higher lands and possessed the quality of being untouchable to fire.

“lo despertaron dos remeros a medianoche: no pudo ver sus caras, pero le hablaron de un hombre mágico en un templo del Norte, capaz de hollar el fuego y de no quemarse. El mago recordó bruscamente las palabras del dios. Recordó que de todas las criaturas que componen el orbe, el fuego era la única que sabía que su hijo era un fantasma.”

He nonetheless knew that his son now existed not because he thought of it, but because he had though him once to Be in a way; prophetically; and he’d pass from being symbol to being real. But what our dream-maker failed to understand here, is whether the image of his son was of flesh or remained an impression. (And what is this question but the endgame of all religious project: to grasp the dualism between flesh and spirit). This crucial omission is what ends up compromising his own integrity in the self-realization/revelation he suffers in the following and concluding passage. Let us wrap this idea for once: abiding to Hume’s logic, the magician-son existed, either in the material world or in the imagination, as an impression cut to the image of his father. He created him on account that he lacked substance, that he was a transparent impression, a ghost; without realizing, it was this very particular quality that he had passed over to his son. In this sense, the magician’s son is a projection of his father-creator in the full stream of the word.

NIGHT 5. PARALLAX

SUBJECTS: PARTICLE & EVENT; POSITIONALITY; THE QUANTUM

“El término de sus cavilaciones fue brusco, pero lo prometieron algunos signos. Primero (al cabo de una larga sequía) una remota nube en un cerro, liviana como un pájaro; luego, hacia el Sur, el cielo que tenía el color rosado de la encía de los leopardos; luego las humaredas que herrumbraron el metal de las noches; después la fuga pánica de las bestias. Porque se repitió lo acontecido hace muchos siglos. Las ruinas del santuario del dios del fuego fueron destruidas por el fuego. En un alba sin pájaros el mago vio cernirse contra los muros el incendio concéntrico. Por un instante, pensó refugiarse en las aguas, pero luego comprendió que la muerte venía a coronar su vejez y a absolverlo de sus trabajos. Caminó contra los jirones de fuego. Éstos no mordieron su carne, éstos lo acariciaron y lo inundaron sin calor y sin combustión. Con alivio, con humillación, con terror, comprendió que él también era una apariencia, que otro estaba soñándolo.”

There is a handful of options to get around this. One of them is to convey this as a circular destiny: History. One creates the other, and another, and another, and History repeats itself. The evolution of our subject’s consciousness always comes insufficient to break with the loops of deception; it is an ever-returning dream. Another is to consider this as a multiverse structured in scales. This is, a bigger entity dreams of a smaller one, and the smaller dreams an even smaller one to existence, while anchored to the dream and devotion of the higher one; in the creation of each new universe, the space and time funnels inwards. This ultimately prompts us with the known metaphor: are we perhaps the dream of a God? The third and most nutritive, for as my inquiry goes, is to consider this as two parallel universes: they simultaneously existed all along, and both ‘father’ and ‘son’ were simultaneously dreaming of and creating one another.

But it is not the idea of the parallel universe that interests me here but the one of parallax perspective. For to regard these as simultaneous realities (or worlds) our imagination demands us to imagine them spatially. This is, each anchored to a situated point in space that is necessarily not the same, and thus, the difference in their positionality blends their perspective with respect to an objective. In Physics, it is a matter of calculus of proximity between two moving positionalities in reference to a concentric point; this is the parallax angle (which by the way, allows us to tie back the problem of perception to the elevated sphere of astral movement from where we had started). The area projected from the parallax angle, which oscillates between their positionalities, in Philosophy, could be referred to as the ‘parallax gap,’ but which only can be considered a gap for it becomes a problem of perception; an epistemological, or in the case of this story, an existential barrier.

I will explain. If the parallax gap is the grey area between their dreams, our dream-creators are trapped in an existential paradox: they can only exist if they are dreamt by the other, but they can’t both exist. The perception of one only exists in the contradiction of the other one’s perception as a point of view. Given the point of view as a fact, the synthesis of their space as a shared one becomes impossible. If we are to consider these dream-creators as both an entity and a universe, one of them must surrender the singularity of itself (its own perception of Self) to allow for the individuation of the other as a possibility. Which explains why, perhaps, our original magician accepts the faith of his finitude, and descends towards death’s labour, for only then, his son might once exist.

The three of these different final interpretations prompt us to regard them as themes of modern Physics—even if they are of the most longstanding preoccupations of existence.—For instance, we could make sense of them, in the fashion of Metaphor, as subjects derived from the possibilities the Theory of Relativity opened to the Scientific and Philosophical paradigms. For this, the concept of the Interval, rather than the Parallax, would be more sufficient. Or even further, we could embark on a quantum analogy; in which, again, events come to substitute matter as the substance of material reality, or at least for its physical study. And how is this not, ultimately, the nature of the final realization of our dream-creator: none of the supernatural creativities he manifested through the narration were as disruptive of his reality as that which annihilated the premise of him being made of flesh and particles (matter) and not of impressions (or whatever substance dreams are made of)—a bundle of perceptions himself. Only once he is embraced by the fire that he realize the absurdity, or in this case, the relativity of the particular laws of the universe he inhabits and creates. For it was event and no longer particle which constituted, substantially, the subject and matter of his physical reality. Further on, the possibility of him ceasing to exist—for quantum theory does not regard motion as an infinite given. In this sense, the history of Philosophy, just like the history of this narration, points to the notion that, in fact, the most modern ‘problems of perception’ are, in their most evolved form, the most ancient ones.

The very last couple of pages of Russell’s lengthy book on the History of Western Philosophy conclude by introducing some relevant questions to approach what he considered was central to the following philosophical paradigm and its challenges. For the time of its publication, six years after the publication of The Circular Ruins, Quantum Theory had entered Philosophy’s scope of interest, or at least his own as a mathematician. He regards it as chief to the continuity of the Philosophical project of ‘logical analysis,’ which he considered himself part of, and prompted that no Philosophy was yet equipped enough to ground Quantum theory, as we now see, even in mathematical terms sufficient for reason. My question is what if we instead attempted so by even more sophisticated verbal sciences like in Poetry or Literature; such would be the case of Borges.

Note

This short story by Borges reads for instance as a Theological text. For it explores subjects of Genesis, Being, Godsmanship, Craftmanship, and Belief and organizes them condensedly in an uppermost prose that is altogether poetic, narrative, and philosophical. No spiritual conclusions but a brief recap:

The evolution of stable ideas—which can be now understood as the evolution of consciousness itself—in the stream of its destiny, requires the abandonment of modes of consciousness no longer useful to stabilize sensible realities; materially, delegates them to the palimpsest of History (impressions), this, as the substance of the Material World; for as the Symbolic World, it leaves them dwelling round the ruins of temples erected for the once devoted, once animated, once imagined.

What is then, the evolution of consciousness if not a cartography of temples sinking back into the stomach of the natural world. Shelters of Belief inhabited by inanimate effigies awaiting to be inhabited themselves, by the air of neurosis, for they can become again the secret of a ritual night.

Žižek, Slavoj. 2006. The Parallax View. Short Circuits. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.